Industrialization Brings Pollution & Protest

Except for the harvesting of salt hay– an industry that existed from the 1600s to the early 20th century– the Meadowlands were mostly considered wasteland. In 1907, Colonel Joseph O. Wright, a federal engineer, declared, “The marsh in its present condition is not only worthless, but is a detriment to public health and a nuisance to the residents of the adjacent upland.” It was “a prolific place for mosquitoes,” containing sewer filth “both obnoxious and unwholesome.”

Over the years, as the region’s population grew, the Hackensack River– water and shore– and the Meadowlands began to play a different economic role.

- Starting in 1901, the water company began constructing dams and reservoirs throughout the Hackensack River watershed.

- Extensive dredging of the Passaic and Hackensack rivers from the late 1800s onward further altered the waters of the Hackensack Meadowlands.

- A series of land reclamation projects began, most notably bridges and highways built across the Meadowlands.

- Factories and warehouses sprung up along the river shore.

- Starting in the early years of the 20th century, pig farms proliferated in the region, giving it one of its best known qualities: Its smell.

- On top of that, the Meadowlands served as a refuse and garbage dump– for both local cities and towns as well as New York City.

At the start of the 20th century, the expanding urban population, combined with increasing prosperity, resulted in a rapidly growing amount of garbage coming out of the cities of north Jersey. Garbage collected by private scavengers or municipal agencies was mixed with clean fill (chemically inert solid materials, such as rocks, gravel, cinders, bricks, and concrete) and used for the new land-making projects. In 1909 a Newark newspaper reported (admiringly) that “New York rubbish is being turned into Jersey soil by scow after scow from Manhattan.”

Often the garbage was simply dumped into the Meadowlands, which was already considered a wasteland. Factories along the Hackensack River also contributed to the pollution by dumping untreated industrial waste. Municipalities often made matters worse by sending raw sewage into the river. There is a story that the town of North Arlington built a canal in the Meadowlands– sometimes called the “poop canal”– to carry its waste out to sea.

Meadowlands were particularly attractive for both legal and illegal dumping. In 1957, almost six acres were given over to landfilling every month in East Rutherford alone. A decade later, the Meadowlands held eleven sanitary landfills that received 29,469 tons of residential, commercial, and industrial waste each week from New Jersey municipalities and parts of New York state. These eleven landfills covered 1170 acres and former landfills covered an additional 1500.

For most of the 20th century, the Hackensack Meadowlands were seen as little purpose other than as dumping grounds. And an obstacle to reach the Hudson River and New York City. That began to change with the construction of the Pulaski Skyway and, later, the New Jersey Turnpike.

For most of the 20th century, the Hackensack Meadowlands were seen as little purpose other than as dumping grounds. And an obstacle to reach the Hudson River and New York City. That began to change with the construction of the Pulaski Skyway and, later, the New Jersey Turnpike.

Given its proximity to New York City, the region needed improved transportation links and it soon became home to an extensive network of roads, rail lines, bridges and tunnels– many of them built during the years between WWI & WWII. For decades, Jersey City had been a railroad town, a transition point for hauling and shipping. With the advent of new roads, bridges and tunnels, trucking took on a larger role in the transportation infrastructure of the 20th century.

The creation of an underground rail system from NJ to NY– “the Hudson Tubes”– in 1908 was just the beginning. In 1927, the Holland Tunnel opened and, a decade later, the Lincoln Tunnel. The Pulaski Skyway opened in 1932. And the NJ Turnpike eastern spur debuted in 1952, the western spur in 1970.

These massive construction/transportation projects were complicated by a number of factors, notably the power of organized labor, urban corruption and organized crime. The story of the building of the Pulaski Skyway exemplifies the intersection of these three things.

While the rise of trade unions in the early years of the 20th century dramatically improved the lives of millions of working people, some construction unions– especially in north Jersey– were infiltrated by members of organized crime. Complicating that already volatile mix was the reign of Jersey City Mayor Frank Hague. Hague was a bundle of contradictions: A popular politician who ran a working class town but hated trade unions, a generous public official who was often a dictator with his own fiefdom.

When construction of the Pulaski Skyway began in the late 1920s, labor activists, notably the Ironworkers, fought to make it a union job. But the builders did not want unions on the job– and they found an unlikely ally in Mayor Hague. By bringing in scabs to build this huge bridge, the business leaders triggered a labor war that led to numerous deaths and much violence. Hague added fuel to the fire by directing the Jersey City police along with hired criminal thugs to attack union activists.

By the time that traffic began to use the Pulaski Skyway– a huge undertaking, which spanned two rivers (the Passaic & the Hackensack)–

it was already obsolete. Yet it was also an engineering wonder, a hulking beauty that traversed the Meadowlands and forever altered the landscape of Hudson County.

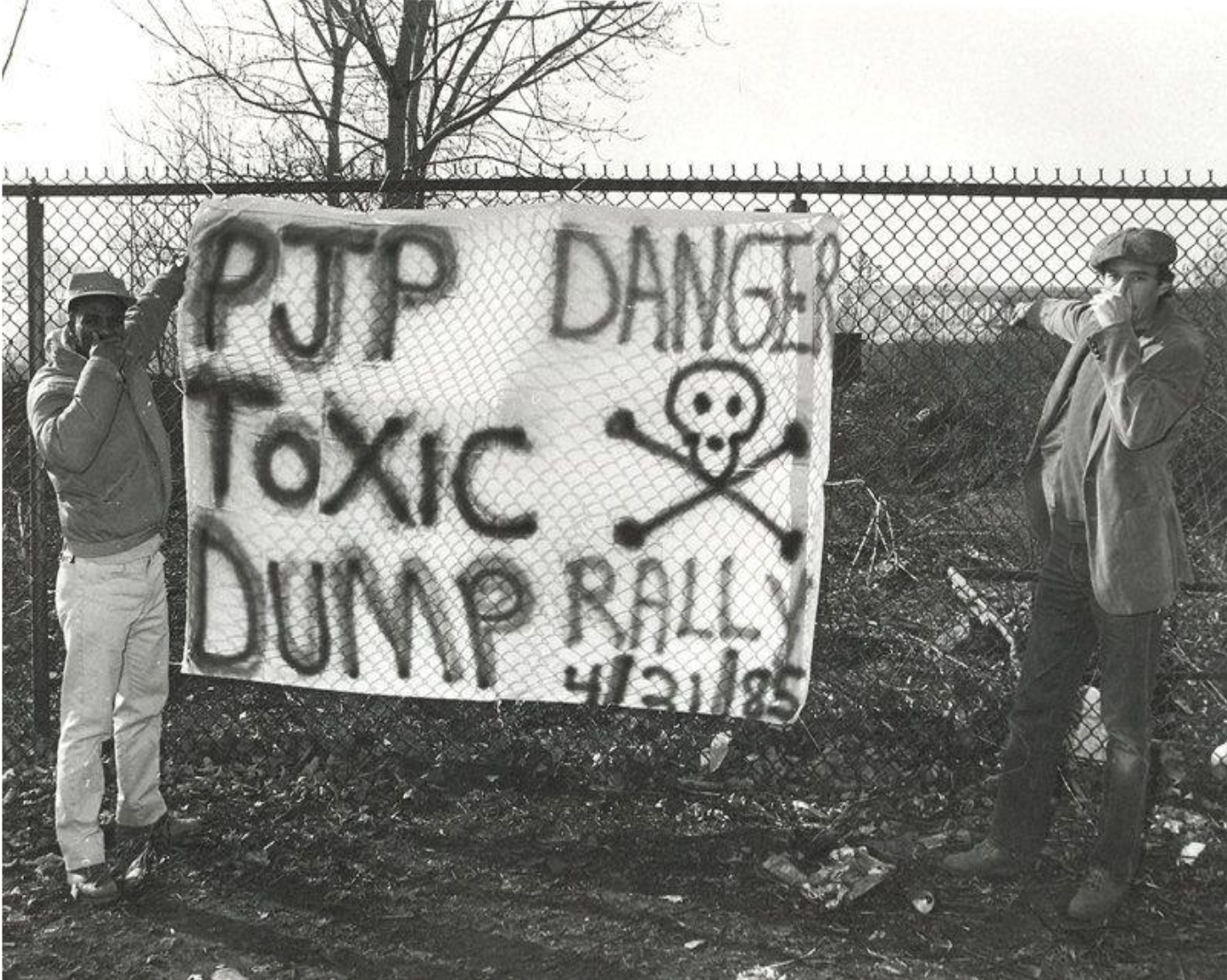

A later example of the devastation brought on by industrialization and corruption in Hudson County– and one much closer to home– was the PJP Landfill in Jersey City. Located on 87 acres of riverfront land, on the west side of Jersey City where Sip Avenue intersects with Routes 1&9, this landfill was one of many where huge amounts of contaminants and other toxic wastes were buried underground.

For years, the PJP Landfill had been the subject of numerous complaints by local residents, the city and the NJ Department of Transportation since 1973. The site was closed in 1977 by state order.

”I would say that we’ve been fighting fires there constantly for the last few years,” said Lieut. Robert McCarthy of the Jersey City Fire Department. Lieutenant McCarthy said it was common knowledge that there had been ”many instances of midnight dumping” at the landfill. He added, however, that no one had ever determined what was burning there.

The principal owner of the landfill site, some 51 acres of it, was the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark, which had been attempting to sell the parcel for years.

The archdiocese and Edwin Seigel, the other principal owner of the area, leased the tract to two men identified as Paul Capola and Philip Moscato. A third man, local political operative John J. Kenny– no relation to a former mayor with a similar name– was involved in the enterprise. The PJP Landfill– aka Brother Moscato’s Dump– gets its name from the first letters of these three men’s names.

Kenny and Moscato were well known to law enforcement. Phil “Brother” Moscato Sr was thought to be a soldier in New York’s Genovese crime family, while Kenny (a former Hudson County Freeholder) was convicted of bribery, extortion and misconduct in office in 1973. Kenny was also part of a scheme to convert more than 100 acres of Hudson County parkland into a landfill operation. A total of 11 men were indicted in that conspiracy, which took place between 1967 and 1970.

It was no secret that organized crime was involved in the carting industry– hauling garbage to landfills– and it was assumed that the PJP landfill was one of those places. When former Teamster President Jimmy Hoffa disappeared in 1975, there was much speculation that his body was dumped somewhere in New Jersey. Recent reports identify a spot near the PJP Landfill, although– despite FBI inquiries– no evidence has surfaced.

More troubling, the PJP landfill was the site of an underground fire that lasted for at least 14 years. The JC Fire Department would put out the fire but it would flair up again later. Residents of the Marion neighborhood, adjacent to the landfill, as well as people in other nearby areas smelled the smoke on a regular basis.

Citizens complained, demonstrations were held, public officials eventually spoke out about this nightmare situation. After years of protest, the time finally came to solve this problem.